The shoulder is a very mobile and shallow joint, best thought of as more of a ‘ball and saucer’ shape, rather than a secure ‘ball and socket’ joint like the hip. It relies on muscles and ligaments to hold the ‘ball’ end of your upper arm (the humerus) onto the ‘saucer’(glenoid) on your shoulder blade. If these become damaged in some way, or if you are naturally very stretchy (hypermobile), then you are likely to experience symptoms of ‘shoulder instability’.

Many people have instability in their shoulder as a result of previous trauma. Perhaps you’ve had a dislocation of your shoulder in the past, or you’ve repeatedly injured it playing sports?

Damage to the muscles and ligaments, (known as ‘soft tissues’), which stabilise the shoulder can also occur over many years of repetitive overhead activity (e.g. if you work with your hands above your head or if you’ve played a lot of tennis).

Sometimes, however, our tissues are naturally a bit lax and overtime the shoulder can become loose.

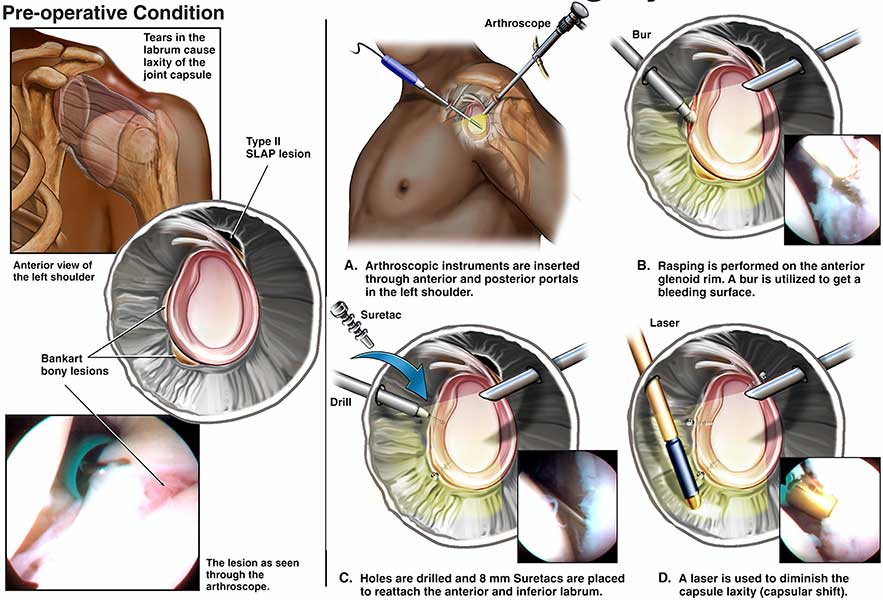

There are other soft tissue structures which are important in maintaining the stability of the shoulder, namely the ‘labrum’ (which is a O-ring of soft cartilage that surrounds the socket, and acts like a stabilising bumper); and also the thick joint capsule that wraps around the shoulder joint itself.

This shallow joint allows the huge range of movement of your shoulders and arms, but at the cost of reduced stability. Many muscle groups are involved in the smooth, uninterrupted movement of your shoulder and, in a healthy joint, they must work together in a coordinated and synchronous manner.

Damage, weakness, or poor function of any of these structures can cause instability.

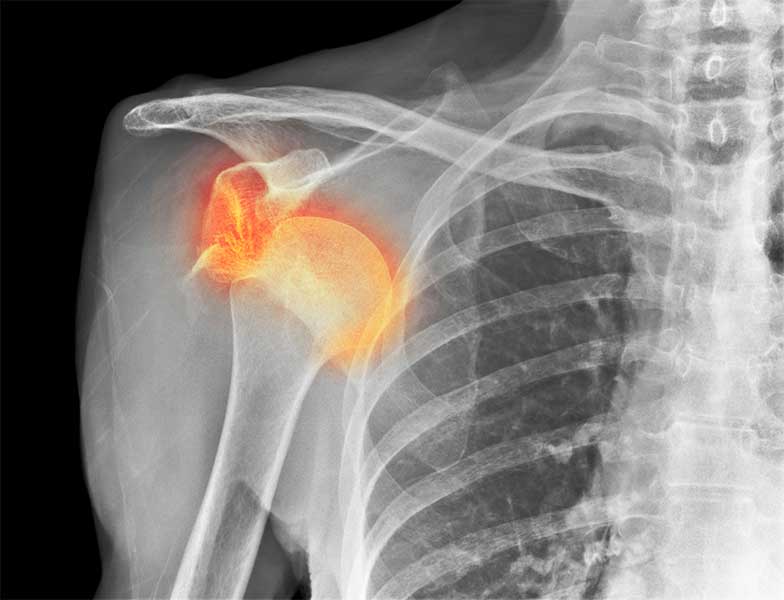

Xray of a dislocated right shoulder

You may have a shoulder which is very unstable, and it literally ‘pops’ out of the socket or dislocates, but for many people, it’s more of a sensation that your shoulder is untrustworthy and you don’t want to put it into certain positions. Sometimes the range of movement in your shoulder isn’t as complete as used to be. Sometimes the main symptom is just pain.

Some kinds of shoulder instability can be successfully treated with physiotherapy or osteopathy, especially if this is due to muscle weakness, or poor coordination between the muscle groups. These therapies will strengthen the shoulder girdle muscles and improve the stability around the shoulder. It’s often worth trying this in the first place.

Some people struggle to have a normally functioning shoulder, despite really good rehab, and then we have to consider surgery.

We know that some people are more likely to need surgery, and also that some people are more likely to benefit from it than others.

If you’ve had a shoulder dislocation and you’re a sporty person under 30 years of age, the chances of you having another dislocation are about fifty-fifty. Those odds are much higher if you are under 20, but If you are over 40 years of age your chance of a re-dislocation drops to well under 10%.

Your need for surgery depends on many things including your age, the number of times your shoulder has dislocated, any ongoing symptoms that you have, your sports and hobbies, and also your work demands.

You and I would talk about your history (have you had several dislocations, or is this the first?), how much trouble the shoulder is giving you (is it occasionally disrupting your sporting performance or is it regularly interfering with your day to day life). We will discuss what damage was seen on the xrays and scans, and finally, what are the demands you place on your shoulder? (are you an elite tennis player, or a Dad with two young kids who plays the occasional round of golf?)

There are two main kinds of shoulder stabilisation – arthroscopic (keyhole) stabilisation, and an open bony shoulder stabilisation (e.g. a ‘Laterjet’ procedure).

This is a day case operation, which means you come into hospital in the morning, and leave by the end of the day. Your shoulder will be numb when you wake up, as we perform a nerve block to make things much more comfortable for you after surgery.

You’ll have three or more very small incisions around your shoulder, so that I can pass a camera and instruments into the shoulder. The aim of the procedure is to restore the anatomy to how it should be – for example, repairing the labrum of the shoulder or tightening the capsule.

Whilst the body repairs itself post-surgery, I’ll ask you to limit the movement of your arm to be within a small range of movement in front of your body – for about 4-6 weeks. I ask that you don’t lift anything heavier than a mobile phone during that time. You can start physiotherapy after surgery to keep your neck and thorax moving well, and the mainstay of rehab starts after the 6 weeks from the time of surgery. Initially it will be gentle movements to restore the range of shoulder, and then around 3 months you can get into some proper strength work.

It can take a good six months to really benefit from the effects of the surgery.

This kind of surgery is very likely to be successful – about 85-90% of patients do very well. There is around a 5-10% risk of dislocation, which is why I ask you to go steady in the beginning.

Sometimes, an arthroscopic procedure may not be enough to give sufficient stability to an unstable shoulder. If you’re highly active in sport, e.g. if you’re a rugby player, I may recommend a procedure called a Laterjet. It might also be required if a chunk of bone was knocked off the socket (glenoid), during a dislocation. The surgery aims to restore the bony part of the socket, by using bone from another area in the shoulder (the coracoid process) and the muscles that attach to it. This reinforces the front part of the socket and stops the head of the humerus moving forwards out of the socket.

Because it involves bone transfer, I carry out the procedure through a longer incision. The recovery from this surgery is similar to the keyhole operation and it will be up to six months before the shoulder can cope with contact sports.

You’ll need to wear a sling for a month or so whilst the bone and soft tissue repair heals, and then strengthening work with a physio begins around 6 weeks after surgery.

The good news is that if you underwent this kind of surgery, the success rate is up to 95%. Sometimes the shoulder may be a little stiffer when trying to turn your shoulder out (external rotation), but most patients find this isn’t an issue for them in their activities.

Every patient is different, and every patient’s needs are different. We’ll take this all into account when discussing whether surgery (and if so, which kind of surgery) is the right thing for you.